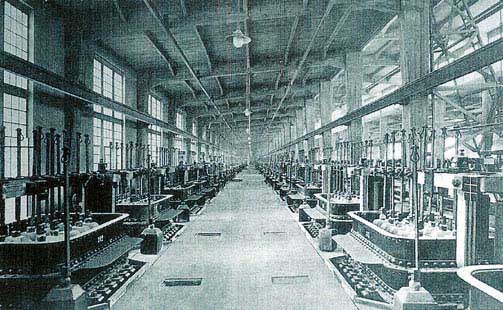

A huge, abandoned structure can be seen from A22 highway, along the right bank of the Adige, in the valley between Lake Garda and Rovereto. It is the buildings of the Alumetal plant – a huge factory complex for the production and processing of aluminum, built between February 1927 and October 1928 by the Milanese industrial group “Montecatini” in agreement with the German company “Vereinigte Aluminum Werke”. The plant was an example of technological innovation of its time, and became a model followed throughout Europe for decades. The plant was one of the first industrial facilities powered by hydroelectric energy. It had an independent power supply from its own hydroelectric power station with a big conveying basin and 4 powerful dynamo turbines.

It was and still remains the largest industrial initiative in lower Trentino and pioneered industrialization in the until them primarily agricultural area. The complex was in operation till 1983, and at its peak time employed 1,224 people. Called simply “Montecatini” by all the locals, the plant also represented the hope of a better life and helped to revitalize an economically depressed and disadvantaged area with new jobs.

To balance the hope, the plant also became a source of controversy and fear, due to aluminum pollution outbreaks that affected the people, animals and plants in the surrounding area in the 1930-es and 1960-es and caused calls for the factory closure by the local farmers. The workers assigned to the ovens were nicknamed the “bakers of the Apocalypse” and had to work in unbearable heat often reaching 60 degrees, with diffusion of fluorine, dioxide and carbon monoxide in the area.

During the Second World War, the “Montecatini” was declared a war factory, and supplied both, Italian and German war industry. The importance of the factory and its workers was such, that they were all protected from the war draft, and remained at their posts. Transportation and supplies during war time were made more difficult, the facility was frequently bombed, and after the shutdown of the factory the surrounding area was mined.

The post-war recovery was slow and painful: the crisis made its effects felt, causing a drastic reduction in the workforce to only 250 workers. The nationalization of electricity in the 1960-es also negatively affected the course of the company. As long as Montecatini was able to have its own plants, this did not have a big financial impact, but with the nationalization the prices increased tenfold. At the same time, competing factories had sprung up around the world and the Montecatini was no longer competitive and susceptible to further production developments. In closed in March 1983.

A prime example of industrial architecture of the early 20th century, the complex is now sadly abandoned and boarded up, but can be admired from outside. Three nice cottages (probably houses of the plant management) on the hill nearby can still be accessed.

Apparently, a renovation project was launched by the Italian government in 2009, aiming to convert the main building of the complex into an exhibition space, and the area around the plant into a park. As of 2023 no construction works have started, but one can remain hopeful.